No doubt you have heard about “pink slime,” the beef additive made from leftover trimmings. According to an article in today’s Wall Street Journal (here), “the additive, which has long been used as a cheap filler in hamburger meat without anyone knowing or caring, has become the latest example of a product to fall prey to a social-media feeding frenzy after celebrity chef Jamie Oliver detailed how it is made in a TV special. Facebook, Twitter and other social media sites took it from there. Supermarkets and school districts across the country have been shunning it after mounting public pressure.”

To counteract that “public pressure,” which Tyson Foods Chief Operating Officer Jim Lochner said is merely a “two-week event,” USDA and governors from several “pink slime” producing states (eg, Rick Perry, Texas) are mounting a counterattack. Iowa Gov. Terry Branstad said “We’re going to consume it. We’ll do everything we can to set the record straight.”

“This is so clearly a movement that’s been driven by consumers,” said Willy Ritch, a spokesman for U.S. Rep. Chellie Pingree (D., Maine), who is pushing for a ban of the filler in school lunches.

USDA chief Tom Vilsack pointed to the difficulty of getting ahead of opposition to a product — even if it is deemed safe by the government — in a world fueled by social media. He also highlighted a disconnect that continues to grow between people and where their food comes from.

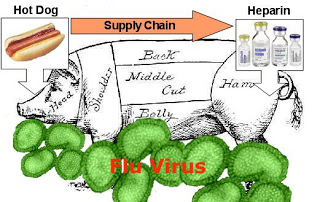

It’s possible that the drug industry will one day face it own “pink slime” crisis because there is also a “disconnect” between consumers and where their drugs come from and the ingredients they contain.

Recently, we have seen cases where active ingredients in medicines have been replaced by miscellaneous substances having no medical benefit and cases where manufacturing problems have led to contamination such as Johnson and Johnson’s problems with children’s medicines (see, for example, “Unsafe Drugs: Is It Counterfeiters or the Supply Chain That’s the Problem?“).

These problems may be glitches in an otherwise safe drug supply chain, but did you know that up to 80 percent of the active ingredients in drugs used in the United States are made overseas? Hopefully, those ingredients meet high standards. Yet up to 149 Americans died in 2007 and 2008 after taking heparin, a blood thinner, contaminated during the manufacturing process in China.

What’s often not mentioned, however, are the “inactive” ingredients in the pills we take. Viagra, for example, contains the following inactive ingredients:

- microcrystalline cellulose

- anhydrous dibasic calcium phosphate

- croscarmellose sodium

- magnesium stearate

- hypromellose

- titanium dioxide

- lactose

- triacetin

- FD & C Blue #2 aluminum lake

Patients are warned to discontinue taking medicines if they are allergic to any of the ingredients.

These ingredients are the “pink slime” of the drug industry. But whereas “pink slime” only constitutes a small percentage of ground beef, these “inactive” ingredients comprise the bulk of the pill’s weight and volume. AND they are probably made overseas with very little FDA supervision.

One of these ingredients may be as controversial to patients as “pink slime” is to hamburger eaters. In fact, this was the case with Johnson and Johnson’s baby shampoo that consumers learned contained cancer-causing chemicals. That issue was big on social media for a while until J&J promised to phase out the product in the U.S. (it has been completely pulled from the shelves in other countries).

The food industry is blaming “misinformation” amplified via social media as the main cause of the consumer backlash against “pink slime.” They have launched a two-pronged campaign to deal with the crisis: (1) issue “corrective” information, and (2) warn of higher prices if “pink slime” is no longer used in hamburger meat.

This sounds similar to how drug companies view social media — i.e., a vast network of “misinformation” about their products. The biggest argument social media advocates use to convince pharma to “engage” with consumers on social media is so that they can be “part of the conversation” and provide “scientifically correct” information about their products to counterbalance all the “misinformation” out there.

The first step is to learn what consumers are actually saying about drugs on social media. The drug industry is actively engaged in that kind of monitoring right now.

![6 Digital Tools at the Center of Healthcare Digitalization [INFOGRAPHIC]](http://ec2-54-175-84-28.compute-1.amazonaws.com/pharma-mkting.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/6DigitalTools_600px-100x70.jpg)