Pharmaceutical sales representatives are faced with increasingly limited access to physicians as many academic medical centers and other healthcare centers adopt conflict of interest policies restricting detailing. This is another benefit versus risk challenge for physicians who need quick access to the latest information about novel drugs. Listen to podcast below:

Read the transcript, which includes charts, below.

According to ZS – a consultancy that provides research on physician access – only 44% of physicians were considered accessible by pharma sales reps in 2016, compared to 47% in 2015, 51% in 2014, 55% in 2013 and 65% in 2012.

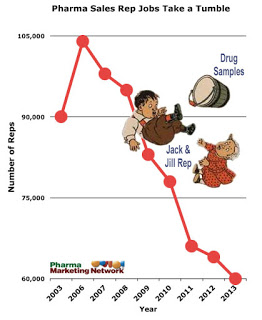

One way that the pharmaceutical industry may dealing with that problem is to reduce the number of sales reps, especially the low-performing reps. In 2006 there were nearly 105,000 reps in the field. By 2014 that number decreased to about 60,000. Although most of that decrease may have been due to a decline in products coming to market during that period, you got to believe that limited access also played a role and continues to do so.

Another tactic is to target prescribers other than physicians, such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants. ZS found that 53% of these prescribers are accessible, compared to 44% of physicians.

Why are more and more physicians limiting access to drug company sales reps?

As pointed out by my friend Rich Meyer at World of DTC Marketing, “[Physicians] are under more pressure than ever to make their practices profitable and really don’t have time for conventional sales reps who are usually trained over one or two days and sent to try and have a peer to peer conversation with them. In addition a lot of drugs really don’t require a sales rep to interact with physicians.”

Meanwhile, a report published by Cegedim Strategic Data found that many physicians like the convenience of non-personal digital detailing such as email communications, video streaming, automated detailing, and webinars which can be viewed on demand.

Consequently, the pharmaceutical industry is in the process of moving its sales force to a smaller structure that is more directly aligned with this new digital reality.

Physicians also have access to many other sources of information about the drugs they prescribe and feel that sales reps do not offer unbiased information, especially when their incentive is a commission based on scripts written.

That is one reason why many academic medical centers have instituted conflict of interest policies restricting detailing by pharma sales reps. These institutions believe that detailing – which most often includes a meal along with with an educational presentation — is associated with higher rates of prescribing expensive brand-name drugs, even when equally effective and cheaper generics are available.

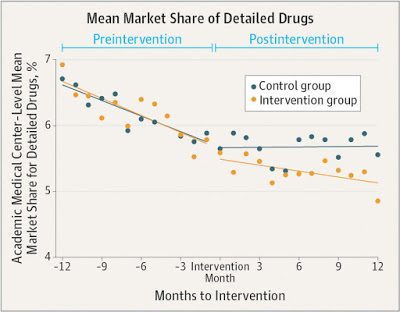

To test that hypothesis, an NIH-funded study looked at how conflict of interest policies affect medication prescribing. The study found that physicians in academic medical centers prescribed fewer of the promoted drugs, and more non-promoted drugs in the same drug classes, following policy changes to restrict marketing activities at those medical centers. While the decline observed was modest in terms of percentage, proportionally small changes can represent thousands of prescriptions.

The decline in prescriptions of detailed drugs was greatest at centers with the most stringent policies, such as bans on salespeople in patient care areas, requirements for salesperson registration and training, and penalties for salespeople and physicians for violating the policies. In 8 of 11 academic medical centers with more stringent policies, the changes in prescribing were significant.

But all this does not mean that the pharma sales rep will soon become extinct. For one thing, many physicians prefer personal interactions with sales reps, especially when they come with food for the staff and free samples for patients.

A JAMA editorial also pointed out potential advantages to pharmaceutical detailing:

“Although physicians can find prescribing information using online resources,” noted the editorial, “one report estimated that it takes nearly 10 years for evidence from reviews, research articles, and textbooks to be widely adopted by the medical community. Pharmaceutical companies have the resources, national workforce, and financial incentive to address this issue, so detailing may accelerate adoption of novel therapies.”

And there are many more novel therapies coming to market these days, especially new drugs for the treatment of cancer. This is of particular concern because many oncologists think the hype (i.e., marketing) from pharma companies about the efficacy of these drugs far outstrips the real world benefits.

An indication that this concern may be justified is research the US Food and Drug Administration, which found that websites for cancer drugs are ten times more likely to include quantitative information about all the benefits of a drug versus all its risks.

So, detailing may accelerate the adoption of novel therapies that do not work as advertised and cost hundreds of thousands of dollars per treatment cycle.

One other factor to consider is the drug industry’s campaign to force the FDA to allow it to provide physicians with off-label information about drugs, especially those novel, ineffective, and costly cancer drugs, which are often prescribed off-label already.

![6 Digital Tools at the Center of Healthcare Digitalization [INFOGRAPHIC]](http://ec2-54-175-84-28.compute-1.amazonaws.com/pharma-mkting.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/6DigitalTools_600px-100x70.jpg)