In the Amarin court case, the court ruled that the company has the right, under the First Amendment, to promote information to health-care professionals about certain uses of the drug Vascepa that aren’t covered by the drug’s FDA-approved labeling — as long as the information is true and not misleading (read “Amarin Wins Off-Label Case Against FDA“). This case is likely to influence new guidance from the FDA regarding off-label drug promotion by pharma marketers.

“Might changes in rules for promotion of off-label indications based on free speech arguments lead to a situation akin to crying fire in a crowded theater?,” asks authors of Commentary published in the recent issue of JAMA Internal Medicine. The authors of the commentary — Chester B. Good, M.D., M.P.H., and Walid F. Gellad, M.D., M.P.H., of the Veterans Affairs Pittsburgh Heathcare System — referred to “compelling evidence” that “off-label prescribing is frequently inappropriate and that prescribing in these circumstances increases the risk for an adverse event substantially.”

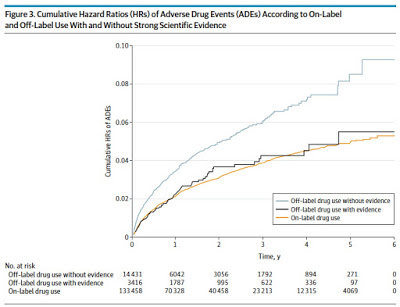

That evidence was presented in a study published in the same issue of the journal titled “Off-label Prescription Drug Use and Adverse Drug Events” (JAMA Intern Med. Published online November 2, 2015. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.6058).

What is the “compelling evidence?”

The authors looked at the off-label use of prescription drugs and its effect on Adverse Drug Events (ADEs) in 46,021 patients who received 151,305 prescribed drugs from primary care clinics in Quebec, Canada. The authors looked at off-label prescription drug use with and without strong scientific evidence.

3,484 ADEs were found in the 46,021 study patients. The overall incidence rate of ADEs for all drugs was 13.2 per 10,000 person-months. The rate of ADEs for off-label use (19.7 per 10,000 person-months) was higher than for on-label use (12.5 per 10,000 person-months), according to the results.

Off-label use that lacked strong scientific evidence had a higher ADE rate (21.7 per 10,000 person-months) compared with on-label use and off-label use with strong scientific evidence (13.2 per 10,000 person-months) had about the same risk for ADEs as on-label use, the study reports.

|

| Click on chart for an enlarged view |

Worse yet, the risk for ADEs grew as the number of prescription drugs the patient used increased, according to the authors. For example, patients using eight or more drugs had more than a 5-fold increased risk for ADEs compared with patients who used one to two drugs.

Good and Gellad also point out that HCPs are ill-equipped to judge off-label “evidence:”

“Even in situations where an off-label indication

has been studied, pharmacokinetics, drug-disease interactions,

and other safety considerations are unlikely to have

been studied systematically to the level required during the

FDA drug approval process. Likewise, few clinicians have the

time or the motivation to review evidence for those off-label

indications to arrive at a balanced assessment of the risks and benefits to support the appropriate use of that drug. Because

clinicians are frequently in error regarding approved drug

indications, patients are unlikely to be advisedwhenthey are

prescribed medications for off-label use in most situations.”

“The FDA and the courts must carefully consider these findings as they contemplate guidance that would relax regulations to permit promotion of drugs beyond their labeled indications,” conclude Good and Gellad.

![6 Digital Tools at the Center of Healthcare Digitalization [INFOGRAPHIC]](http://ec2-54-175-84-28.compute-1.amazonaws.com/pharma-mkting.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/6DigitalTools_600px-100x70.jpg)