It is well-known that space constraints inherent in search ads and social media applications such as Twitter prevent the pharmaceutical industry from disclosing FDA-required important safety information (ISI) in ads/messages that promote Rx drugs for indicated uses. There may be ways around this (see here and here and here), but without specific social media guidelines from the FDA, the drug industry is reluctant to use the workarounds.

It turns out that space limitations may also be a factor in preventing physicians from disclosing conflict of interest (COI) ties to the pharma industry when they use Twitter and other social media to communicate with patients, especially about medical research.

In a commentary published online in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, Matthew DeCamp, M.D., Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine’s Division of General Internal Medicine, “argues that some physicians use social media to give advice to patients and the public without revealing drug industry ties or other information that may bias their opinions,” reports HealthCanal.com (here). “Without serious efforts to divulge such information – standard practice when publishing in medical journals and recommended in one-on-one contacts with patients – DeCamp says consumers are left in the dark.”

“As physicians and patients increasingly interact online, the standards of appropriate behavior become really unclear,” says DeCamp, who also holds a fellowship at the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics. “In light of norms of disclosure accepted throughout medicine, it’s surprising that major medical guidelines fail to adequately address this issue.”

Decamp notes that one reason for this may be difficulty in in disclosing within the space constraints of social media. A generic disclosure such as “The author has no conflict of interest to report related to this tweet” uses up 70 of the allotted characters and leaves little room for other content such as patient support messages or research information.

In other cases — such as in medical journals and in office settings — physicians must disclose conflicts, although sometimes they don’t. And such lacks of disclosure CANNOT be blamed on “space limitations.”

Speaking of disclosures in the office setting, according to the article “when doctors prescribe a blood pressure medication, professional guidelines say they are ethically bound to tell patients if they have any financial relationship – such as receipt of consulting fees – with the company that manufactures the drug.”

I have some personal experience with physicians that do not reveal possible conflicts when prescribing drugs to patients: my Doctor — who has received payments from Pfizer in 2010 — wanted to switch me to from a generic Pravachol to brandname Lipitor to control my high cholesterol level (see “Occupy Pfizer! Protest It’s Deal to Block Sales of Generic Lipitor! #OccupyPFE“).

“While some professional guidelines do recommend disclosure in social media,” DeCamp says, “they don’t lay out how it should be done, while many ignore the topic altogether. The history of conflict of interest in medicine is such that you don’t want to be late to the table,” DeCamp says.

I agree that guidelines for physician use of social media should lay out how to disclose conflicts of interest. I’d love to see the guidelines that do this (see below) because they may be the model for FDA guidelines on how pharma should disclose ISI via social media/search ads that promote Rx drugs. The problem is, will physicians adhere to such guidelines any better than they have adhered to “real world” disclosure guidelines?

P.S. I’ve looked at one example of guidelines for physicians use of social media that addresses COI: The Federation of State Medical Boards “Model Policy Guidelines for

the Appropriate Use of Social Media and Social Networking in Medical Practice” (find it here).

Regarding disclosure of COI, this document states: “At times, physicians may be asked or may choose to write online about their experiences as a health professional, or they may post comments on a website as a physician. When doing so, physicians must

reveal any existing conflicts of interest and they should be honest about their credentials as a physician.”

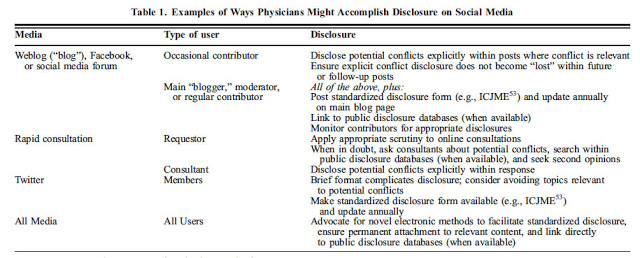

This comes no where close to helping physicians figure out how to actually do this in a social media setting such as Twitter. DeCamp, at least, provides some specific examples of ways that physicians might accomplish disclosure on Social Media (click for a larger view):

![6 Digital Tools at the Center of Healthcare Digitalization [INFOGRAPHIC]](http://ec2-54-175-84-28.compute-1.amazonaws.com/pharma-mkting.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/6DigitalTools_600px-100x70.jpg)