A new report from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), “Promotional Spending for Prescription Drugs” (find it here), counterintuitively suggests that “drugs with little competition are likely to be marketed to consumers far more aggressively than drugs with a lot of competition” (NY Times). According to the report:

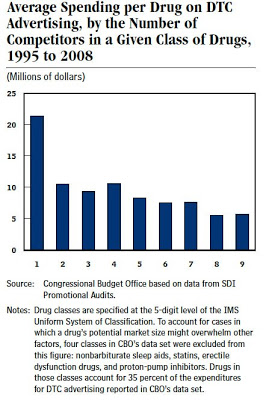

“Pharmaceutical manufacturers tend to spend more, on average, on DTC advertising for drugs that have few or no direct competitors (meaning there are few other drugs that treat the same condition using the same mechanism) than on products with numerous alternatives. Excluding some classes of drugs with the highest-selling and most advertised drugs — where a drug’s potential market size might overwhelm other factors in setting a marketing plan — the data analyzed by CBO show that average spending per drug on DTC advertising generally declines as the number of competitors in the same class increases (see Figure below). When a class includes more drugs, pharmaceutical manufacturers tend to spend less, on average, on DTC advertising because the benefits of that advertising (higher sales) may be diffused among the other drugs in the class.”

“A monopoly,” says the NY Times reporter, “reaps any benefits of its advertising alone.”

The report notes that physician detailing expenditures do not exhibit the same relationship between average spending and the number of competitors in a drug class.

The thinking is that if you promote a drug having competitors, it’s just as likely that a competitor drug will be prescribed as will be your drug. This interpretation is consistent with other data — from ad agency sources — which concludes that DTC advertising does NOT result in consumers asking their doctors for the advertising drug by brand name (see “Advertisers Don’t Know How DTC Works. Say wha?“).

It appears that DTC may be used as a tool to maximize profits during the period when the drug enjoys a monopoly. Higher prices can be charged during this period because there is no competition. Hence, a link between DTC and high drug prices (see also “Did State Medicaid Programs Finance Plavix Direct-to-Consumer Advertising?“).

Some critics of DTC advertising say that drug companies should wait one, two, or three years before advertising new drugs to consumers. The rationale is that new drugs may have unknown risks that may not be seen until used for a few years.

PhrMA’s DTC Principles waffles on the issue: “In order to foster responsible communication between patients and health care professionals, companies should spend an appropriate amount of time to educate health professionals about a new medicine or a new therapeutic indication and to alert them to the upcoming advertising campaign before commencing the first DTC advertising campaign.”

A few pharmaceutical companies have agreed to a voluntary 6-month or 1-year moratorium on DTC advertising for new drugs. Some experts say that DTC typically does not begin immediately after approval in any case.

However, a moratorium of 2 or 3 years would drastically reduce the profitability of those drugs that are “first-in-class”; ie, those without competition in the first few years on the market. I suspect that this is the main reason why drug companies are resisting efforts by lawmakers to impose a long moratorium on DTC. By offering a voluntary 6-month moratorium, drug companies seem to be compromising but really are not offering anything they have not alread been doing.

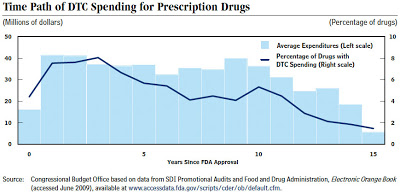

The chart below for CBO shows that promotional expenditure usually peaks 1 to years after approval for marketing.

![6 Digital Tools at the Center of Healthcare Digitalization [INFOGRAPHIC]](http://ec2-54-175-84-28.compute-1.amazonaws.com/pharma-mkting.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/6DigitalTools_600px-100x70.jpg)