- “Marketing with sanofi-aventis US. These tweets are my opinion alone and not the opinion of any organization with which I am affiliated.” — @ABoyle129

- “Director, Social Media for Bristol-Myers Squibb, former journalist and co-author: How to Say It: Marketing with New Media. Opinions and tweets here are my own.” — @alisonwoo

- “passionate on healthcare. changing world w/ social innovations. 365 breakfast tweets project. all tweets are my own and do not represent my employer’s view.” — @anjelikadeo

Is this enough to keep you out of hot water in case you inadvertently make a comment that your boss or legal department doesn’t like?

Most pharma companies probably already have guidelines for employees such as Roche’s “7 Rules for personal online activities,” the first of which states:

“Be conscious about mixing your personal and business lives. There is no separation for others between your personal and your business profiles within social media. You must be aware of that. Roche respects the free speech rights of all our employees, but you must remember that patients, customers and competitors as well as colleagues may have access to the online content you post. Keep this in mind when publishing information online and know that information originally intended just for a small group can be forwarded on.”

Another group of health professionals — physicians — also must be conscious about mixing their personal and business lives while using social media. Institutions, medical boards, and physician organizations worldwide have promulgated recommendations for physician use of social media that are similar to Roche’s “7 Rules.”

A common theme among these recommendations is that physicians should manage patient-physician boundaries online by separating their professional and personal identities. A viewpoint published yesterday in JAMA, however, contends that “this is operationally impossible, lacking in agreement among active physician social media users, inconsistent with the concept of professional identity, and potentially harmful to physicians and patients.” (see “Social Media and Physicians’ Online Identity Crisis”; JAMA. 2013;310[6]:581-582).

“Resolving the online identity crisis,” the authors contend, “requires recognizing that social media exist in primarily public or potentially public spaces, not exclusively professional or exclusively personal ones. Boundaries exist; they simply are not drawn around professional and personal identities, nor can they be. When a physician asks, ‘Should I post this on social media?’ the answer does not depend on whether the content is professional or personal but instead depends on whether it is appropriate for a physician in a public space.”

The same is true for pharmaceutical executives. Roche cautions its employees in Rule #2:

“You are responsible for your actions. You are ‘speaking’ publicly and your contribution may stay searchable and retrievable for a long time to a broad audience – both internally and externally. Anything that brings damage to our business or reputation will ultimately be your responsibility. This does not mean that you should refrain from any activity, but that you should use common sense and take at least the same caution with social media as with all other forms of communication.”

From personal experience following many pharma executives on Twitter, I can attest that not once have I seen an inappropriate comment posted — apart from dissing a particular baseball team that I am a fan of. Although I have heard of one pharma employee — a salesperson — who “inadvertently” tweeted about an off-label use of Botox (see “Allergan ‘Badly Let Down’ by Employee Tweet“).

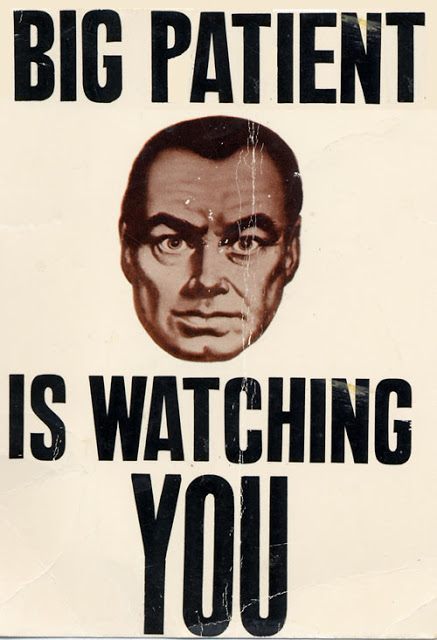

Back to physicians and the ethics of physicians posting personal views on social media sites. The authors note that patients are watching: “Patients — many of whom come to appreciate their physicians as individual persons through office photos, books, and conversations — might miss out on certain benefits when their physicians choose to separate their personal identity online. A depersonalized online interaction might be less effective than it could be, for example, at normalizing difficult, shared emotions or at expressing empathy. It might also reduce trust in the patient-physician relationship more generally if patients sense that their physician is intentionally hiding something.”

Abandoning the effort to separate personal and professional identities online has advantages, the authors claim. “First, it does not ask physicians to do the impossible, nor does it rely on an incorrect concept of professional identity. Second, it is likely to be more accepted by active physician social media users, in part by building on the vast experience physicians already have in navigating public spaces, rather than asking them to do something new or unfamiliar. Absent this approach, the professional transgressions motivating guidelines will persist and the potential benefits of social media will remain unrealized.”

The same can be said for pharma professionals, many of whom may be reluctant to venture into social media because of a “social media identity crisis.”

What’s Your Social Media Implementation Plan?

Before you find yourself in a social media crisis, you should have a social media implementation plan. But what are the action items for implementing your plan? This survey presents a number of actions that may be appropriate and seeks your input on how important these or other items might be in developing a plan. Take the survey now — afterward, you will be able to see the summary of all responses to date. No comments or other identifying information is included in the summary.

![6 Digital Tools at the Center of Healthcare Digitalization [INFOGRAPHIC]](http://ec2-54-175-84-28.compute-1.amazonaws.com/pharma-mkting.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/6DigitalTools_600px-100x70.jpg)