Even though pharmaceutical marketers are NOT exploiting social media to the degree that industry consultants and agencies would like them to, they have learned one important lesson from social media: people trust people like themselves more than they trust company spokespeople or even so-called experts. That may be why you are seeing more and more direct-to-consumer (DTC) ads on TV and in print that feature real patients who offer testimonials to the advertised Rx drug.

Pfizer, for example, is currently running Lipitor and Chantix ads in which real patient users of the drug tell their stories. Previously, Pfizer, like so many other drug companies, employed actors that portrayed physicians or “real” physicians in these ads. That, however, backfired spectacularly when it was discovered that one physician spokesperson — Dr. Jarvik — was not actually a practicing physician.

Dan Hill, President of Sensory Logic, Inc., contends that there is a problem with this. Hill was guest on my Pharma Marketing Talk BlogTalkRadio show yesterday — October 26, 2010 — where claimed that two-thirds of the ads are “not so good, especially with the would-be testimonials” of real, everyday patients.

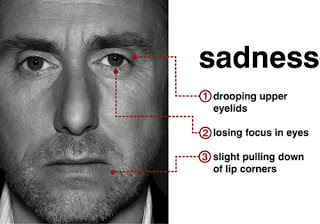

Hill bases reached this conclusion by applying “Facial (Action) Coding” techniques to analyze the effectiveness of the ads. If you have ever watched FOX’s “Lie to Me” drama series, you may familiar with this technique, which involves analyzes facial expressions to determine the emotional state of a person.

Facial coding was first developed by Dr. Paul Ekman — who is an adviser for the show “Lie to Me” — and is featured for 30 pages in Malcolm Gladwell’s “Blink.” Hill claims that this non-invasive tool — which breaks down 23 facial expressions (Action Units) into 7 core emotions — allows him to help clients understand the emotional connection of their market research efforts (for example, what consumer are really feeling about their TV commercials, print ads, websites, as opposed to what they say.)

Hill says the goal of Facial Coding is “Get[ting] the Right Emotions at the Right Time.” That sounds like a nice complement to the often-heard axiom of “getting the right message to the right audience at the right time.”

Hill offered one example of how the “wrong” emotion exhibited by an actor in a GSK TV ad sent the wrong message to the audience.

At second 17 in the timeline, the test audience — claims Hill — had a “fear reaction.” There was really no intent by GSK to illicit fear, so Hill was stunned. The verbal comments from the test audience couldn’t explain it, so Hill used his facial coding ability to look at the facial activity of the actors. “Lo a behold,” said Hill, “at second 17, the male lead showed fear on his face. My suspicion,” said Hill, “was that he forgot his line for a nano second.” Emotions are so contagious that this flash of fear on the actor’s face that the audience “[went] there with him.”

With regard to real patient testimonials in TV commercials, Hill says that the actors often look “uneasy, stilted, and don’t show the emotions that are meant to be shown.” This, Hill claims, hamstrings the commercial so that it is not as effective as it could be.

You Audience Has Left the Building

Another interesting point that Hill made was in regard to the voice-overs (VO) of TV Rx ads. VOs usually occur during the “fair balance” (ie, side effect disclosure) portion of the ad, which may consume 30% of the total running time. Hill said that “the sad truth is that many voice overs kill the commercial. It is the moment when marketers think they are bringing home the message, but instead the audience has left the building.” Perhaps the reason why voice overs are used most often during the fair balance portion of the ad is precisely to drive the audience away from the ad once they have already been exposed to the benefit portion.

“A monologue simply does not work for people,” said Hill. A Cialis ad was cited by Hill as doing a “very good job with the legalese at the backend of the commercial.” The ad keeps switching between the man and the woman delivering the fair balance message. “At least that variation, going from the male to the female and then back to the male, at least make it more noticeable,” claims Hill.

One observation in closing is this: current social media lacks the dimension of facial coding and using real patients in social media campaigns retains the advantages of credibility without the disadvantages that Hill pointed out.You can listen to my conversation with Hill using this BogTalkRadio widget:

![6 Digital Tools at the Center of Healthcare Digitalization [INFOGRAPHIC]](http://ec2-54-175-84-28.compute-1.amazonaws.com/pharma-mkting.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/6DigitalTools_600px-100x70.jpg)