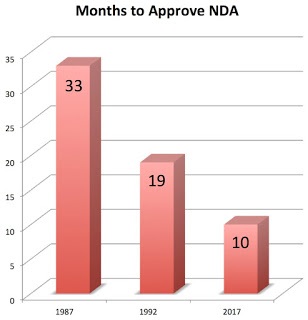

Back in March, 2017, President Trump “called on the Food and Drug Administration to speed the approval of drugs to treat life-threatening diseases, deriding the agency’s current process as ‘slow and burdensome’”(here).

According to Dr. Michael Carome, Director, Public Citizen’s Health Research Group, president Trump’s claims that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s approval process for medical products is “slow and burdensome” and “keeps too many advances … from reaching those in need,” reflect complete ignorance about the FDA’s current regulatory schemes for ensuring that medications and medical devices are safe and effective (here).

In an analysis published in The BMJ last week, Thomas Marciniak, a retired team leader within FDA’s Division of Cardiovascular and Renal Products, and Victor Serebruany, a professor at Johns Hopkins University, attempt to debunk some of these claims, reports RAPS (here).

“This crude depiction ignores industry’s contribution to the clock after clinical trials are completed but before the FDA receives the formal application,” they write. “It may be possible to accelerate drug approvals in other ways, such as changing processes earlier in the development programme, before the end of the pivotal trials,” they write, while cautioning that lowering FDA’s standards to speed reviews “may prove costly for patients and healthcare budgets.”

Of course, the real issue is how long it takes drug companies to come up with the evidence in order to submit an NDA (New Drug Application) to the FDA. Pharma has won the battle to get FDA turnaround times down to the bare minimum. It now has to turn to allowing drugs to be approved with less evidence. That’s really what this is all about. FDA is just a convenient scapegoat, IMHO.

There is one solution to alleviating FDA’s “slow and burdensome” approval process and getting potentially life-saving drugs to patients.

Even before Trump’s comments before Congress, vice president Pence met with several families and encouraged them to lobby Congress for a federal “Right to Try” law, which would allow people with fatal illnesses to gain access to experimental medicines, even though they are not enrolled in a clinical trial. “Your goal is admirable, said Ed Silverman, author of Pharmalot. “Unfortunately, though, you’re peddling false hopes” (here).

Do you think this is a good idea? Why? Why not? Take my survey, which asks your opinion on this topic.

![6 Digital Tools at the Center of Healthcare Digitalization [INFOGRAPHIC]](http://ec2-54-175-84-28.compute-1.amazonaws.com/pharma-mkting.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/6DigitalTools_600px-100x70.jpg)