I have very little in common with Jamie Reidy, the author of the book “Hard Sell: The Evolution of a Viagra Salesman,” which is a tell-a-lot-but-not-all about pharmaceutical sales (see my review of this book in the upcoming February, 2006 issue of Pharma Marketing News). For one thing, Reidy is a Generation X’er (the cohort born between 1965 and 1980) and I am a boomer (the cohort born between 1946 and 1964).

The differences between Generation X’ers and boomers may help explain the decrease in pharma sales force effectiveness over the years.

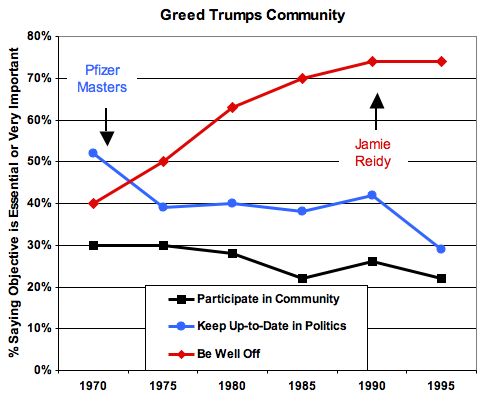

One difference to consider concerns the importance of wealth vs. community as motivating factors for these two generations. A UCLA survey of college freshmen cited in the book “Bowling Alone” showed that Generation X’ers — who were freshman in 1990 — were much more concerned with achieving wealth than boomers who were freshman in 1970 (see chart). “Greed,” says author Robert D. Putman, “trumps community” for Generation X’ers.

Greed — i.e., the promise of a high salary, bonuses, expense account, and company car — motivated Reidy to interview for the Pfizer sales rep job in the first place. Throughout the book he exhibits other Generation X traits, such as the frequent conversational use of the word “dude” as in “Dude, I need a little favor” and “Dude, pass the Viagra!” He is also frequently at odds with boomers, including his father and managers at Pfizer, especially when it comes to work ethic and other traditional values of older generations.

Reidy mentioned a Pfizer survey that revealed an “alarming high attrition rate” among reps with 4 to 6 years of service. In contrast to this are the Pfizer Masters — sales reps whose sum of Pfizer service plus age equals at least 65 years and who have tremendous sales success. “Most of the Masters,” quips Reidy, “still comb their hair the way they did when they first saw Rebel Without a Cause in the movie theater.”

Greed alone may not be enough to motivate successful sales people. Maybe a little more sense of community — caring about patients, for example — might help. Nowhere in Reidy’s book do I see any evidence that he really cared about patients. He was trained that “Most benefits [of drugs] revolved around saving a physician or her staff time and hassle”, not about treating patients. And, according to Reidy, “nothing makes pharmaceutical sales people crazier than news of ‘tab cutting'”, a practice common among poor an elderly patients who cannot afford the high cost of drugs. “Dude, where’s your compassion?”

![6 Digital Tools at the Center of Healthcare Digitalization [INFOGRAPHIC]](http://ec2-54-175-84-28.compute-1.amazonaws.com/pharma-mkting.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/6DigitalTools_600px-100x70.jpg)