AbbVie, Astrazeneca, Eli Lilly, GSK, Merck, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, plus others have submitted comments to the FDA regarding its plans to research animated spokes-characters in DTC Drug Ads (see Federal Register Docket ID: FDA-2016-N-0538).

Merck was not impressed: “While the proposed collection of information may be interesting to learn, it may not have practical utility for the general public and may be unnecessary for the proper performance of FDA’s functions.”

Regeneron expressed a similar concern; i.e., “the results from this study should not be used to guide or influence FDA’s current thinking on the use of animation in DTC ads.”

But FDA is sticking to its guns.

“On the contrary,” says FDA in response, “this particular study has the potential to directly influence policy in an area that we have no prior research on. Although one research study cannot answer all questions, we believe we have designed the study in such a way that we will be able to provide information on the issue of animation in DTC ads. Because there is no previous research of this kind, this will be an informative study that will help FDA develop guidance and policy in the future, should the research reveal a need to.”

Meanwhile, The Advertising Coalition, representing national trade associations whose members prepare and deliver advertising through television, newspapers, magazines, the Internet, whipped out its 1st Amendment gun: “[T]his study must be viewed through the lens of two Supreme Court rulings that explicitly protect Commercial Speech, including advertising. In particular, the FDA must be mindful of the Supreme Court’s ruling in Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinary Counsel, which held a state regulation of an advertising illustration unconstitutional and subject to strict scrutiny.”

But the comments I found most interesting had to do with the “Uncanny Valley” Hypothesis and measuring the “eeriness” of certain animated ads.

Both Astrazeneca and Eli Lilly objected to study Question 26, which asks test subjects to rate the eeriness of ads using rotoscoped characters. In 2007, a Pfizer Celebrex TV ad featured rotoscoped characters (see screen grab above).

“We feel that question 26 should be deleted because it is a leading question,” said Astrazeneca. “If not deleted, change ‘eerie’ to ‘strange’.” Lilly also said the question is leading, “as it directs participants to respond only negatively about their perceptions of the character.”

FDA’s response to AZ: “Given the uncanny valley [my emphasis] theory concerning rotoscoped images (Ref: Clayton, R.B. and G. Lesher, “The Uncanny Valley: The Effects of Rotoscope Animation on Motivational Processing of Depression Drug Messages.” Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media. 2015;59(1):57-75), we feel it is crucial to maintain this specific question about the eeriness of the character.”

Further, in response to Lilly, FDA said: “We agree that this is an unusual question and may seem off putting without context. However, previous research has compared live action and rotoscoped action in advertisements and has determined that people feel uncomfortable with rotoscoping because it is very similar to what we expect from live renditions, but not exactly. This theory is called the uncanny valley theory. Question 26 comes directly from this previous research and we feel strongly that we need the question as it is to ground our comparison of live action and rotoscoping in the prior literature.”

What the heck is the “uncanny valley” theory??

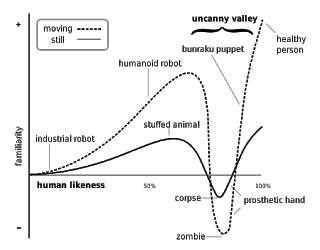

According to the authors of the research cited by FDA, “The Uncanny Valley Theory, proposed by Mori (1970), provides a theoretical explanation as to why viewing animated images or messages may evoke a strange viewing experience. Originally linked to Freud’s 1919 concept entitled ‘The Uncanny’ (‘Das Unheimliche’), the uncanny valley theory assumes that mismatches among human and nonhuman features strike discords among the observer, and the overall effect is ‘eerie’. This dip in the observer’s affinity for the object is called the ‘uncanny valley’.” [See figure.]

“That is, when human features look and move almost, but not exactly, like natural human beings, it evokes a negative, or repulsive response. Mori theorized that such an effect, or revulsion, is similar to viewing an ‘animated corpse’ (Mori, 1970/2012). The uncanny valley is now commonly applied to ‘‘characters in animated films and videogames to which viewers cannot relate because of flaws in how they were computer-modeled, animated, and rendered. In the case of viewing rotoscoped-animated characters in depression drug commercials, the uncanny valley theory would predict that viewers would reject animated characters once they begin feeling ‘eerie’ or begin to experience unpleasant emotions due to the uncanny human realism of the animated characters.”

Speaking of animated corpse, I think that’s an apt description of the Pristiq wind-up doll shown here. Pfizer, which did not submit comments to the FDA regarding this study, is responsible for this definitely uncanny human realism of an animated character in its Pristiq ad (here). I find the doll eerie (not strange). In this case, that’s the whole point because the sad doll represents how it feels to be depressed – like a walking corpse! But, in the end, the doll transforms into a happy doll – still eerie, IMHO.

BTW, FDA will use ads for dry eye and psoriasis, not depression, in its study.

GSK, which also discounts the usefulness of the study, made some comments about animation in drug ads that are worth repeating here:

“In addition to animation being used to ‘grab attention, increase ad memorability, and enhance persuasion,’ there are other important reasons a sponsor might choose to use animation in DTC advertising:

- Animation can be a very effective way of educating consumers about complex conditions in simple ways.

- Animation can be used to help consumers quickly identify that an ad is relevant to them/their condition.

- Animation is a tool that can de-personalize an ad to help make it more relevant to more people with the medical condition.

“The proposed research may serve to oversimplify “animation” as one homogeneous type of ad technique. In reality, there are a number of types of animation (black and white line drawing, very sophisticated anthropomorphized people, illustrated storybook characters, cartoonish characters etc.). Additionally, the proposed research fails to account for the difference between ads that are 100% animation or ads that are partially-animated. Therefore, given the narrow focus of the research, it is unlikely to yield any general conclusions about the use of animation.”

FDA seemed a little perturbed by comments suggesting that it’s research is unscientific and should not be used to inform its guidelines. In its comment to Regeneron, FDA said: “Although this is the first study to directly examine animation in DTC ads the way we have proposed here, the research we have designed is robust and well controlled. As trained research psychologists, we adhere to the highest standards in terms of rigorous control, prespecified hypotheses, appropriate statistical analyses, and reasonable and responsible interpretations. Our research undergoes many internal and external reviews before and after data collection, including a stringent OMB review (of which public comment is a part), multiple levels of internal clearance, and peer review at well-respected academic journals in relevant fields. Although FDA never exclusively uses the findings of one scientific study to make policy decisions, the quantitative research we conduct is one part of the calculus that FDA uses to inform policy decisions.”

![6 Digital Tools at the Center of Healthcare Digitalization [INFOGRAPHIC]](http://ec2-54-175-84-28.compute-1.amazonaws.com/pharma-mkting.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/6DigitalTools_600px-100x70.jpg)