I get periodic emails from Bob Ehrlich, Chairman of DTC Perspectives, Inc., giving his opinion on various direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertising issues.

Although I often do not agree with Ehrlich on many issues, I value his perspective and often respond to him via this blog (read, for example, “Are We at the Saturation Point Viz-a-Viz Celebrity Pharma Endorsements?“). We’ve even had a head-to-head podcast debate (listen to “Are Drug Marketers an Endangered Species?“).

In a recent email missive, Ehrlich calls FDA’s recently proposed study of deception in DTC ads (read “Another FDA Study: Can HCPs and Consumers Recognize “Deceptive” Drug Website Promotions”) “the most puzzling FDA DTC study proposed to date.”

“I have problems with this proposed study on many fronts,” says Ehrlich. He also has at least ten questions about this study:

Questions:

- How are consumers supposed to know what is in the approved label to decide what is deceptive?

- So FDA will have consumers play detective like those games where you see two photographs slightly altered to spot the changes?

- Does FDA want consumers to be the vanguard of regulation and report claims they think are deceptive?

- Is FDA going to staff a hotline to receive consumer complaints?

- Consumers expect the claims in an ad to be vetted by FDA so what is the study goal in purposely putting in deceptive claims to see how misled is the consumer?

- What possible help could this study provide in future promotional guidances?

- A study that proves consumers can be deceived and might be unable to know they are being deceived proves what?

- Is FDA trying to prove consumers who do not know what is in the approved label can be easily fooled by rogue drug companies?

- If a drug makes deceptive efficacy claims, it is going to be more appealing to consumers. Hello, my new drug cures cancer. You interested?

- Is this deeper understanding using mock deceptive ads going to make FDA a better regulator?

I’d like to respond to some of these questions. But first, let me do some fact checking of statements Ehrlich makes.

#1: In relation to Q 5 Ehrlich states: “the consumer relies on FDA to prevent deception. Drug ads are already the most scrutinized ads in America. Most ads are pre-cleared well before they run. Consumers expect the claims in an ad to be vetted by FDA.”

FALSE: This implies (or perhaps I infer) that FDA vetts and “pre-clears” (i.e., approves) drug ads before they run. Perhaps consumers believe that the FDA approves drug ads before they run, but that is a mistaken belief. FDA does NOT “pre-clear” ads before they are run. Ehrlich certainly should know this, so it is a puzzle as to why he propagated this myth.

The FDA only requests drug companies to submit ads before or at the time they are first run. “Except in unusual instances,” says FDA (here), “we cannot require drug companies to submit ads for approval before they are used. Drug companies must only submit their ads to us when they first appear in public. This rule is the same whether the ads are aimed toward healthcare providers or consumers. This means that the public may see ads that violate the law before we can stop the ad from appearing or seek corrections to the ad.”

Some companies submit ads to the FDA well before thay are run to give the FDA time to review the ads and provide “advisory,” non-binding comments. If FDA does not raise any red flags, the drug company assumes the ad has been “pre-cleared.” However, this does not mean that some other FDA reviewer will later – after the ad runs – find fault with the ad and issue a notice of violation letter.

#2: Ehrlich also states in Q 5 that “Most warning letters are over subjective elements like distracting music or scenes, not over false claims.”

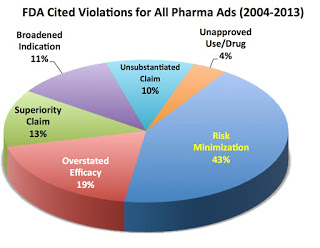

FALSE: Regardless of music or scenery in drug ads, most FDA warning and notice of violation letters cite outright objective deception such as “unsubstantiated claims” (10% of cited violations), “risk minimization” (40% of cited violations), “overstated efficacy (19% of cited violations), “broadened indication” (11% of cited violations), and “superiority claims” (13% of cited violations). These numbers are from an EyeOnFDA analysis of 235 warning letters sent by FDA between 2005 and 2013. Only recently have we seen a couple of UNUSUAL letters focusing exclusively on subjective elements (read, for example, “FDA Cites TV Ads for ‘Compelling’ ‘Attention-Grabbing’ Distractions That Undermine Communication of Risks”).

#3: Ehrlich states that “In 20 years of television DTC ads, there are a only handful of ads that overstated efficacy.”

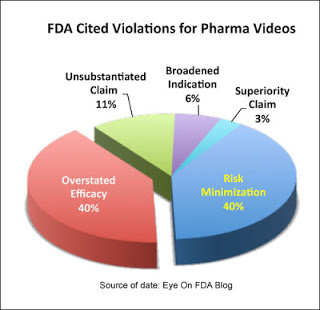

TRUE? If we are just talking about TV ads, this may be true. But when Mark Senak at EyeOnFDA blog looked at FDA letters citing violations in other pharma marketing videos, 40% of the violations were classified as overstated efficacy.

It also does not take an FDA expert to recognize when drug ads are overstating efficacy, which is what FDA is trying to prove or disprove with the study under question. Recently some TV ads have been criticized by knowledgable healthcare professionals for overstating efficacy (read “Oncologists Say Cancer Drug Advertising Fosters Misinterpretation of Efficacy by Patients”). But I would be remiss if I did not point out that other “Oncologists Are Not Concerned About DTC ‘Over Promising’ Efficacy.”

#4: Ehrlich states in relation to Q 6 that “False claims are already prohibited. Each branded ad must meet strict FDA criteria for fair balance.”

TRUE but this statement is misleading because some drug ads do not adhere to FDA’s “strict criteria for fair balance” and “omission” or “minimization” of risk information is by far the most commonly-cited violation in 235 FDA warning letters issued between 2005 and 2013.

This leads me to my responses to Questions 2, 3, 4, and 10: YES! YES! YES! and YES!

Sorry, Bob. I don’t have any answers or comments relevant to questions 7, 8, and 9, which are mostly rhetorical or cannot be answered in any case.

![6 Digital Tools at the Center of Healthcare Digitalization [INFOGRAPHIC]](http://ec2-54-175-84-28.compute-1.amazonaws.com/pharma-mkting.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/6DigitalTools_600px-100x70.jpg)