On February 4, 2004, the FDA issued long-awaited draft guidance documents designed to improve communications to consumers and health care practitioners about health conditions and medical products. One document was titled “Brief Summary: Disclosing Risk Information in Consumer-Directed Print Advertisements.”

“Our new regulatory guidance,” said Mark B. McClellan, M.D., Ph.D., FDA Commissioner at the time, “provides new direction to sponsors on how to provide higher-quality health information to the public, based on recent evidence on what works and what doesn’t in drug promotion” (read “FDA Draft Guidance for Print DTCA: Less than Feared“).

But now even NEWER evidence – and complaints from the pharma industry – forced the FDA to issue a “revised draft guidance” titled “Brief Summary and Adequate Directions for Use: Disclosing Risk Information in Consumer-Directed Print Advertisements and Promotional Labeling for Human Prescription Drugs,” which you can find here (Docket No. FDA-2004-D-0500).

Released on February 9, 2015, this revision was ELEVEN years in the making. Compared to that, the four years FDA took to issue draft social media guidelines was lightening fast.

The guidelines address the requirement under provisions of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act), which require that an advertisement for a prescription drug to disclose each side effect, warning, precaution, and contraindication from the labeling. This is referred to as the “brief summary requirement.”

So what’s new in the guidelines?

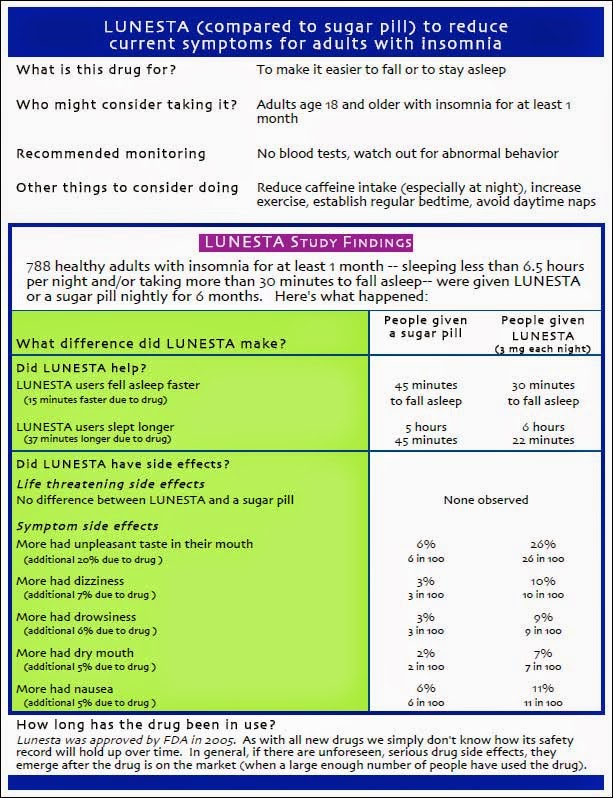

In effect, the guidelines jettison the “traditional approach” to fulfilling the brief summary requirement and replaces it with what the FDA calls the “Consumer Brief Summary.”

FDA now believes that the “traditional approach,” in which the full package insert (PI) has generally been used to fulfill the brief summary requirement (see, for example, “Future of Drug Print Ads“), is not optimal for consumer-directed prescription drug print advertisements and promotional labeling pieces because many consumers “lack the technical background to understand some of the information as described in the PI. Additionally, information that may be of limited use to consumers (e.g., clinical pharmacology) is included.”

FDA goes so far as to warn pharma advertisers NOT to use the full PI in print ads:

“FDA strongly recommends against the use of the traditional approach to fulfill the brief summary requirement in consumer-directed advertisements, an approach in which risk-related sections of the PI are presented verbatim, often in small font.”

In addition, FDA says it “does not intend to object if a firm does not include ‘each specific side effect and contraindication’ from the PI in the brief summary in consumer-directed print advertisements.”

Here are some of FDA’s specific recommendations:

- use consumer-friendly language in all consumer-directed materials (duh!) – avoid scientific/medical jargon and use a “conversational tone”

- the consumer brief summary should be presented visually in a manner designed for ease of use by consumers; e.g., use “signals” such headlines and subheadings

- the consumer brief summary should provide “clinically significant” information on the “most serious and the most common risks” associated with the product and omit less pertinent information

- the most frequently occurring Adverse Reactions should be included in the consumer brief summary

- include a statement reminding consumers that the information presented is not comprehensive

|

| Click on image for an enlarged view. |

According to the FDA, participants who viewed the brief summary information in a format similar to the OTC Drug Facts box had “better risk recall, greater confidence in their ability to perform tasks related to the brief summary, more positive attitudes toward the ad, and greater preference for the format than did those who viewed a traditional, but consumer-friendly, version of the brief summary.”

Again, it all depends on what “facts” should be included. What FDA refers to as “Consumer Brief Summary” could very well end up being shortened to overly-simplified “Consumer BS” geared to ensuring “more positive attitudes toward the ad.”

The docket has been re-opened for comments here.

![6 Digital Tools at the Center of Healthcare Digitalization [INFOGRAPHIC]](http://ec2-54-175-84-28.compute-1.amazonaws.com/pharma-mkting.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/6DigitalTools_600px-100x70.jpg)