When the November 15, 2009, AARP Rx Watchdog Report revealed that manufacturer prices for widely used brand name drugs have climbed dramatically over the last year, despite a negative general inflation rate, many people — including several Congressmen — suspected “price gouging” in anticipation of future cost containment under new healthcare legislation.

But there may be another type of drug “price gouging” going on — deliberately raising drug prices to cover the cost of Direct-to-Consumer advertising (DTCA)!

A new study published in today’s issue of the Archives of Internal Medicine (“Costs and Consequences of Direct-to-Consumer Advertising for Clopidogrel in Medicaid”; Arch Intern Med. 2009;169[21]:1969-1974) offers evidence that drug price increases are engineered to cover the costs of DTCA.

The authors of the paper examined pharmacy data from 27 Medicaid programs from 1999 through 2005. They analyzed changes in the number of units of clopidogrel (Plavix) dispensed, cost per unit dispensed, and total pharmacy expenditures.

What’s interesting about this study is that it was able to compare volume and costs before and after DTCA initiation. Plavix has been marketed extensively using DTCA starting in 2001, several years after it was initially released. There was no DTCA for Plavix from 1999 to 2000. From 2001 to 2005, U.S. spending on DTCA for Plavix exceeded $350 million, an average of $70 million per year. “This preliminary analysis of an ideal case study,” said the authors, “allowed us to estimate changes in prescribing after the initiation of DTCA, while controlling for existing pre-DTCA trends.”

“One could surmise that DTCA might lead to increased expenditures via 3 mechanisms,” noted the authors. These are:

- Increased use as a result of marketing directed to patients would lead to increased total pharmacy costs.

- Regardless of increased use itself, pharmaceutical companies might try to offset the expense of DTCA—more than $5 billion in 2006—by increasing the price of the advertised drug.

- If manufacturers expect or receive an expanded indication for a particular product, they may both increase price and initiate DTCA.

According to DTC expert, Bob Ehrlich, “DTC is a tactic to improve sales not the fundamental driver of sales. For blockbuster drugs like Lipitor DTC may account for an incremental 1-2% of sales. The best DTC campaigns may provide a higher boost to sales, maybe up to 10% of the total for lifestyle drugs” (see “Business Week on DTC“).

In other words, experts like Ehrlich support mechanism #1 above and contend that DTCA boosts sales volume and use of the advertised drug. Therefore, drug prices are not linked to DTCA according to these experts.

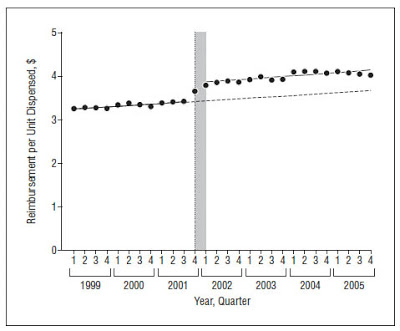

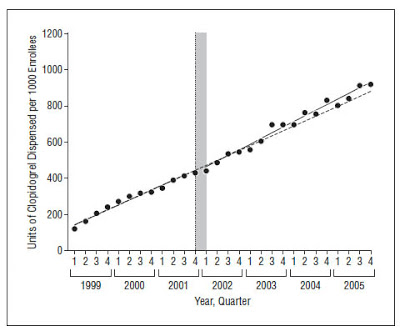

The authors of the Plavix/Medicaid study, however, did not find a spike in sales after initiation of Plavix DTCA. What they did find was a spike in unit cost, which supports mechanism #2. In essence, the drug companies that market and sell Plavix – sanofi-aventis and BMS – may have raised the price it charges Medicaid for Plavix in order to cover the costs of direct-to-consumer advertising! This is an interesting finding, especially if it can be generalized for all DTC-promoted drugs. It certainly should be of interest to the federal and state governments that pay for Medicaid drug benefits!

Here are the “smoking gun” data charts published by the authors:

An interesting factoid:

The authors estimate the overall increase the 27 state Medicaid programs paid for Plavix amounted to $207 million. These 27 programs account for 67% of all Medicaid enrollment. If we expand the estimate to cover the other 33% of Medicaid enrollees, then Medicaid may have paid over $300 million in increased costs, which covers practically all of the $350 million spent on Plavix DTC during the period studied!

![6 Digital Tools at the Center of Healthcare Digitalization [INFOGRAPHIC]](http://ec2-54-175-84-28.compute-1.amazonaws.com/pharma-mkting.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/6DigitalTools_600px-100x70.jpg)