Lately there’s been a lot of talk about pharma marketers “joining the conversation” about their products in social networks and blogs (see, for example, “Social Media: Ask Permission to Join the Conversation First or You Just Might Get Your Ass Kicked!“).

Lately there’s been a lot of talk about pharma marketers “joining the conversation” about their products in social networks and blogs (see, for example, “Social Media: Ask Permission to Join the Conversation First or You Just Might Get Your Ass Kicked!“).

However, I am not sure that joining the conversation in a completely transparent way is in the nature of pharmaceutical marketers. We only need to look at what happens in the “real world” of pharma-consumer (patient) interaction to understand how pharma is likely to approach online social networks.

The case of “Electroboy” (Andy Behrman) vs. Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS) offers some insights. According to a story in the Wall Street Journal (see “A Celebrity Patient’s Backing Turns Sour for Drug Company“):

“In 2004, Bristol-Myers held a retreat for 1,250 sales representatives, to prepare them to market a powerful psychiatric drug for a new use — bipolar disorder.

“Pharmaceutical companies have taken to paying patients to help promote their products. In the case of Andy Behrman and Bristol-Myers, the relationship has backfired.

“A video of Mr. Behrman, a 42-year-old bipolar patient, filled a gigantic screen. He recounted how a Bristol-Myers drug, called Abilify, had changed his life. Unlike other medicines he had tried, Abilify had no side effects, he said. The testimonial drew a standing ovation.

“But Mr. Behrman says he had only taken the drug for four days before the video was filmed. He says he later experienced side effects — including dazed spells and agitation in his legs — unpleasant enough that he stopped taking the drug within a year. He says he eventually told several company employees privately about the difficulties he was having with the drug.

“Yet, he continued to talk glowingly about Abilify throughout 2004 and 2005, to sales representatives and other company employees, as well as psychiatrists hired by the company as consultants. In all, Bristol-Myers paid him $400,000.”

Despite the fact that the relationship between BMS and Behrman backfired, hiring patients, consumers, physicians, and celebrities as spokespeople is still a favorite ploy of pharmaceutical marketers.

Until recently, PhRMA’s “Guiding Principles for Direct to Consumer Advertisements About Prescription Medicines” did not address the use of paid endorsements. In the December 2008 revision, this principle was added:

Where a DTC television or print advertisement features a celebrity endorser, the endorsements should accurately reflect the opinions, findings, beliefs or experience of the endorser. Companies should maintain verification of the basis of any actual or implied endorsements made by the celebrity endorser in the DTC advertisement, including whether the endorser is or has been a user of the product if applicable.

This and the other principles, however, do NOT address the use of celebrities at live events or on the Internet. Nor does the “celebrity” principle apply to the use of ordinary citizens/patients who are not “celebrities.”

Pharmaceutical companies are free to pay well-respected patient members of social networks to speak glowingly about their products in online conversations. Jacke Barrette, CEO of WEGO, calls these ordinary people who influence the opinions of others “Consumer Opinion Leaders” (COLs; see “WEGO Health: Empowering Health Consumer Opinion Leaders“). Malcolm Gladwell, author of the book Tipping Point, calls such people “Mavens.”

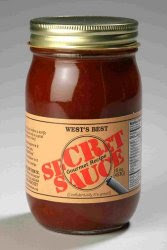

COLs are pharma’s “secret sauce” for social media marketing. COLs have the benefit of already being part of the “conversation,” which neatly solves the marketer’s problem of how to “join the conversation.”

I imagine there are hundreds of patients out there on social networks who would gladly take thousands of dollars from pharmaceutical companies to be spokespeople as part of online branded drug or disease awareness campaigns. This may be going on right now and we’d never be the wiser — unless, of course, another “Behrman” with grandiose ideas of his worth arises and tells all!

FTC is well aware of the trend and potential abuse of using COLs as paid spokespeople. On April 13, 2009, Advertising Age reported: “As part of its review of its advertising guidelines, the FTC is proposing that word-of-mouth marketers and bloggers, as well as people on social-media sites such as Facebook, be held liable for any false statements they make about a product they’re promoting, along with the product’s marketer.”

![6 Digital Tools at the Center of Healthcare Digitalization [INFOGRAPHIC]](http://ec2-54-175-84-28.compute-1.amazonaws.com/pharma-mkting.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/6DigitalTools_600px-100x70.jpg)