CommonHealth’s MBS/Vox division conducted a study of 440 physician-patient conversations, which according to industry reports — and I’m quoting a story in the October issue of Pharmaceutical Executive (PE) Magazine — “sought to determine how often discussions about prescription brands were taking place…” in doctors’ offices.

That’s not quite true. The study actually sought to show — and does show — that “it doesn’t appear that a high percentage of patients are going to the doctor and directly [emphasis added] saying, ‘I saw X brand on TV and that’s what I want.’ ” This is a direct quote from Joseph Gattuso, president of CommonHealth’s MBS/Vox division.

Can you see the difference between how PE characterizes the study’s goals and what the study actually shows? Gattuso is not talking about how often discussions about brands take place in the doctor’s office — he’s talking about whether or not the patient mentions seeing the brand advertised. In other words, CommonHealth is focusing only on how often DTC is mentioned in doctors’ offices, not how often brands are mentioned.

Mentioning DTC ads vs. mentioning drugs by brand name; that’s a big difference. But the trade press — including PE Magazine — is spinning the study to prove a point rather than to help understand how DTC works. The point they want to prove is that DTC does not cause consumers to ask for more expensive medicines. The study proves no such thing, yet CommonHealth is aiding and abetting the misinterpretation of its study by denying us access to their data.

Perhaps if we could see CommonHealth’s data, we might be able to draw our own conclusions. Unfortunately, the data that were released by CommonHealth to me, to the trade press, and to the general public, doesn’t include raw numbers, not too much about the methodology (ie, linguistic rules applied), and doesn’t include any data about how often branded discussions take place (as opposed to branded discussions in which DTC advertising is mentioned).

I reported on this study back in September (see “Advertisers Don’t Know How DTC Works. Say wha?“). At that time, when I asked CommonHealth analysts for more data, they demurred. That, of course, only led me to believe that they had something to hide. They did mention that a report was submitted to the FDA.

Surprisingly, the report wasn’t available through the FDA or Federal Register Web sites. I had to submit a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request for it. I hate when I have to do an FOIA request, especially when everyone — FDA included — is calling for more transparency! But it’s a cherished right I have as an American citizen and I made the request so you don’t have to.

An FOIA request is a bureaucratic hassle and it takes some time to get results. I made my request on September 18, 2006 and got the report on November 2, 2006. Not quick, but at least a quicker turnaround than I got from PhRMA (see “PhRMA’s Response – PRwise, it Stinks!“). If you want a copy, it’s here (Docket2005N-0354). FREE!

[BTW, the FDA is charging me a $2.60 copying fee. That’s about $0.10 per page. I figure their margin on copying FOIA documents is around 50%!]

I was expecting to find raw data, multiple tables, lots of detail about methodology, etc. You know, all that stuff that a “data-driven” agency like the FDA wants.

unfortunately, all I got was a paper copy of a cover letter and a slide deck. At first, I didn’t think this exercise would be blog-worthy, but I did end up finding a couple of interesting tidbits.

First, in the CommonHealth cover letter to the FDA (see page 3 of the documents), I notice the involvement of John Kamp, Executive Director of the Coalition for Healthcare Communication, a gaggle of advertising agencies, which believes that “the patient is the decision-maker only with respect to whether a practitioner should be approached” (see “DTC without the Risk“).

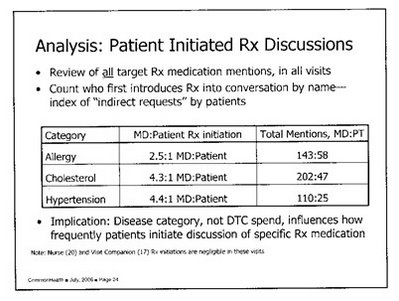

But the interesting bit of information — which CommonHealth never released to the public nor to the press that I know of — can be found on the 12th page of the slide deck printout, which I reproduce here (download the complete slide deck for a better copy):

Here, we can see that there were 585 mentions of a brand name drug either by the doctor or the patient during the 440 visits recorded. True, the doctor initiated the discussion in the vast majority of cases (455 or 78% of the mentions). Yet the patient mentioned a brand name drug first in 130 cases or 22% of the mentions. That’s a far greater percentage than the 1.0% to 3.9% numbers that CommonHealth focuses on in its PR campaign to make its case that DTC does not play a role in patients requesting advertised drugs.

Here, we can see that there were 585 mentions of a brand name drug either by the doctor or the patient during the 440 visits recorded. True, the doctor initiated the discussion in the vast majority of cases (455 or 78% of the mentions). Yet the patient mentioned a brand name drug first in 130 cases or 22% of the mentions. That’s a far greater percentage than the 1.0% to 3.9% numbers that CommonHealth focuses on in its PR campaign to make its case that DTC does not play a role in patients requesting advertised drugs.

Obviously, DTC advertising plays a huge role in raising awareness of new treatments among consumers. That role is often cited by the industry as a beneficial effect of DTC advertising. If DTC and PR, which is just another arm of DTC advertising (see “Marketing Disguised as PR“), are primarily responsible for raising awareness of drugs in the minds of consumers, then, by extension, whenever a patient mentions a drug by name in a doctor’s office, that mention is due to the influence of advertising.

Despite all the obfuscation and spinning of the data, no one is really fooled. But the sad part is that there is a call out for the FDA to establish an advisory board of communication experts that will help it design better methods of communicating drug benefits and risks to consumers. This advisory board will include experts from agencies such as CommonHealth. If this study is any indication on the kinds of advice the FDA will be getting from communication experts, then I anticipate a lot of blog-worthy fodder in my future!

![6 Digital Tools at the Center of Healthcare Digitalization [INFOGRAPHIC]](http://ec2-54-175-84-28.compute-1.amazonaws.com/pharma-mkting.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/6DigitalTools_600px-100x70.jpg)