Yesterday, the American Medical Association (AMA) adopted a new policy on “Professionalism in the Use of Social Media” (find the press release here) According to the AMA, this policy aims at “helping physicians to maintain a positive online presence and preserve the integrity of the patient-physician relationship.”

Looking over the AMA guidelines, I find that this policy, like all such policies — including the policies of pharma companies regarding employee use of social media — (1) was developed after the cow has left the barn (ie, many physicians are already using social media; see, for example, this recent Pharma Marketing News article: “Physician-Generated Content on Social Media Sites“) and (2) has an underlying negative view of social media and physician-generated content.

The last principle, for example, states:

“Physicians must recognize that actions online and content posted may negatively affect their reputations among patients and colleagues, may have consequences for their medical careers (particularly for physicians-in-training and medical students), and can undermine public trust in the medical profession.”

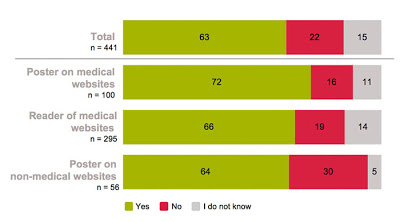

A recent survey of physicians (see here) using social networks performed by DocCheck — a major European physician portal and social network — asked “Have you ever read and learned important medical information from content posted by other healthcare professionals on DocCheck, or on a similar online healthcare professional network?” Sixty-three percent (63%) said “Yes” (see chart below). Obviously, the majority of physicians learn from “physician-generated content” posted on social networks like DocCheck.

Another AMA social media principle states:

“When physicians see content posted by colleagues that appears unprofessional they have a responsibility to bring that content to the attention of the individual, so that he or she can remove it and/or take other appropriate actions. If the behavior significantly violates professional norms and the individual does not take appropriate action to resolve the situation, the physician should report the matter to appropriate authorities.”

What “authorities” does the AMA have in mind? The AMA? I see this as a slippery slope.

Its interesting that “dialogue” is not mentioned in the AMA policy. It’s always been a tenet of social media that open discussion among users will self-regulate user-generated content and that no “official” sanctions need to be applied except in the most extreme cases.

The issue of correcting mis-information on social networks also came up as one of the questions FDA asked about pharma’s use of social media (see “Should Pharma Companies Correct Drug Misinformation Posted on 3rd-Party Social Media Sites?” and “Are There Special Cases for Correcting Misinformation on Social Media Sites?“). The consensus seems to be that the correction of misinformation by pharma should not be mandated by FDA regulators. Also, people who responded to my FDA survey generally felt that information aimed at healthcare professional audiences required even less need for corrective action because of the presumed ability of these audiences to appropriately assess and filter the information.

One commenter said this about information posted by physicians:

“Health care professionals should have the correct information as determined by consensus and should be reminded to not misrepresent the information. They have more influence if it is known that they are professionals so they can cause greater damage from misinformation. Some people calling themselves health professionals are misrepresenting their real qualifications. Again, as an example, the scienceblogs will review the qualifications of an individual calling themselves a ‘health expert’ while also commenting on the distortions of the information.”

![6 Digital Tools at the Center of Healthcare Digitalization [INFOGRAPHIC]](http://ec2-54-175-84-28.compute-1.amazonaws.com/pharma-mkting.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/6DigitalTools_600px-100x70.jpg)