Are Some DTC Print Ads Too Educational and/or Persuasive? FDA Plans to Do Two Studies to Find Out

By John Mack

The FDA often describes itself as a “data-driven” agency. That’s an understatement as far as approving drugs for marketing is concerned. FDA’s Office of Prescription Drug Promotion (OPDP) also wants to rely on robust data before it issues guidelines for advertising. Consequently, it often holds public hearings to learn from experts what research may be necessary to answer its questions about the impact of direct-to-consumer (DTC) or health professional advertising.

The FDA often describes itself as a “data-driven” agency. That’s an understatement as far as approving drugs for marketing is concerned. FDA’s Office of Prescription Drug Promotion (OPDP) also wants to rely on robust data before it issues guidelines for advertising. Consequently, it often holds public hearings to learn from experts what research may be necessary to answer its questions about the impact of direct-to-consumer (DTC) or health professional advertising.

Sometimes, however, it seems that the FDA uses studies to “table” or delay issuing guidelines. See, for example, “FDA’s Proposed Web Study Will Further Delay Social Media Guidelines” and “A Cautionary Tale for Anyone Expecting FDA Social Media Guidelines Any Time Soon.”

Recently, two FDA studies were in the news: “Disease Information in Branded Promotional Material” and “Effect of Promotional Offers in Direct-to-Consumer Prescription Drug Print Advertisements on Consumer Product Perceptions.” The focus of both these studies will be on print ads.

Do Mixed Disease Awareness/Branded Ads Confuse Consumers?

Usually, pharmaceutical DTC ads are either “disease-awareness” ads or “branded ads.” The former ads discuss a particular disease or health condition, but do not mention any specific drug or device or make any representation or suggestion concerning a particular drug or device. These ads, which are focused on consumers, are also called “help-seeking” ads.

Unlike drug and device promotional labeling and prescription drug and restricted device advertising (i.e., “branded ads”), disease awareness communications are not subject to the requirements of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act and FDA regulations.

Disease-Awareness Ads are Less Persuasive

“Some research,” notes the FDA, “has shown that disease awareness advertising is viewed by consumers as more informative and containing less persuasive intent than full product advertising.”

According to Patrick Kelly, former President of Pfizer US Pharmaceuticals, who testified at a 2005 FDA public hearing on DTC, “general disease-awareness and help-seeking ads do not drive patients to the doctor to anywhere near the degree that information about a solution or a potential solution will.” This finding is “not well-understood,” said Kelly.

“What we have found,” Kelly said, “is that if your express just that you should be aware that there is a medical condition or a disease that you should worry about, it doesn’t generate as much action as if you then say there might be potential solutions that you should consult with your provider about. So it is the other connection that is important for motivating action.”

Nevertheless, at the time, Pfizer announced it had allocated a portion of their media budget a financial amount “equivalent to one major medicine” to address general public health as a “stand-alone brand” without mentioning any drug brand. Part of this sum was used to develop help-seeking ads or unbranded disease-awareness ads.

In a discussion of this topic on Pharma Marketing Network, an expert said:

“The reason that consumers respond to branded ads more than unbranded disease awareness ads is primarily not because of a branding effect, although branding is powerful in its own right. Consumers do not respond to a disease awareness ad because they are being made more aware and knowledgeable about a ‘problem’ and less aware and knowledgeable about a ‘solution’ to address that problem. Simply: Who in their right mind wants to know about having a problem for which there is no solution?”

New Ad Format: Mixing Disease Information and Product Promotion

To address this problem, some pharmaceutical marketers have come up with a new type of DTC ad: a branded ad that includes more disease information than a typical branded ad.

The FDA is concerned that too much disease information may “confuse” or mislead consumers, so the agency recently published a notice in the Federal Register (find it here) in which it outlined a study it plans to do to determine if consumers confuse educational information about a disease with specific product claims approved by the FDA in such ads.

“Sponsors [pharmaceutical companies] may choose to include disease information in their full product promotions,” says FDA. “Such information is designed to educate the patient about his or her disease condition. However, in some cases a full description of the medical condition may include information about specific health outcomes that are not part of a drug’s approved indication… When broad disease information accompanies or is included in an ad for a specific drug,” says the FDA, “consumers may mistakenly assume that the drug will address all of the potential consequences of the condition mentioned in the ad by making inferences that go beyond what is explicitly stated in an advertisement.”

FDA cites as an example a hypothetical ad that mentions “diabetic retinopathy,” which is damage to the eye’s retina that occurs with long-term diabetes. “…the mention of diabetic retinopathy in an advertisement for a drug that lowers blood glucose may lead consumers to infer that the drug will prevent diabetic retinopathy, even if no direct claim is made. The advertisement may imply broader indications for the promoted drug than are warranted, leading consumers to infer effectiveness of the drug beyond the indication for which it was approved.”

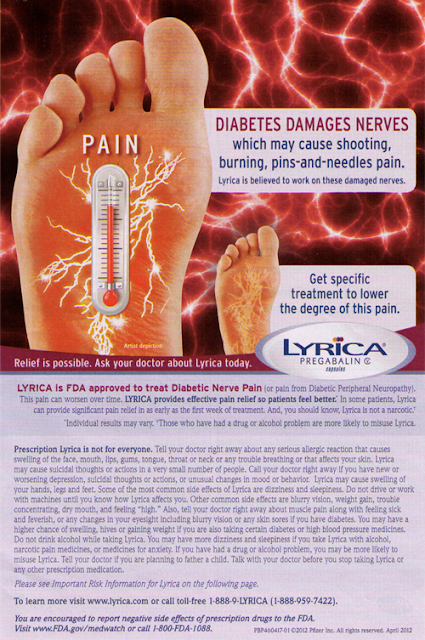

LYRICA Print Ad as a Case Study

I couldn’t find a diabetes-related print drug ad that mentioned “diabetic retinopathy,” but I did find one in the June 24, 2012, issue of Parade magazine that informed me that “Diabetes Damages Nerves.” That ad (shown below) promotes Pfizer’s drug Lyrica, which is indicated for the treatment of “Diabetic Nerve Pain.” It is NOT indicated to prevent nerve damage caused by diabetes.

What I see when quickly glancing at this ad is “DIABETES DAMAGES NERVES” (all caps), then “PAIN,” (also all caps) and, finally, “LYRICA” (also all caps). If I were a typical consumer with diabetes, I might think that LYRICA prevents damage to my nerves, which would be an incorrect assumption.

Drug Ads & Coupons The FDA is concerned that the use of sales promotions such as free trial offers, discounts, money-back guarantees, and rebates in direct-to-consumer (DTC) prescription drug ads “artificially enhance consumers’ perceptions of the product’s quality” while also resulting in an “unbalanced or misleading impression of the product’s safety.” To test whether or not this is true, the FDA will soon start yet another study focused on Rx print ads: “Effect of Promotional Offers in Direct-to-Consumer Prescription Drug Print Advertisements on Consumer Product Perceptions” (see Federal Register Notice archived here).

The FDA is concerned that the use of sales promotions such as free trial offers, discounts, money-back guarantees, and rebates in direct-to-consumer (DTC) prescription drug ads “artificially enhance consumers’ perceptions of the product’s quality” while also resulting in an “unbalanced or misleading impression of the product’s safety.” To test whether or not this is true, the FDA will soon start yet another study focused on Rx print ads: “Effect of Promotional Offers in Direct-to-Consumer Prescription Drug Print Advertisements on Consumer Product Perceptions” (see Federal Register Notice archived here).

The history of this study is long and mysterious. I first blogged about it 2006; read “FDA, Coupons, and Sleep Aid DTC Ads.” Shortly after that the Federal Register notice regarding the study was “yanked” (see “FDA Backs Down on Coupon Study“). Also, the Advertising Age and Wall Street Journal articles cited in those posts can no longer be found in the archives.

In September, 2011, however, the proposed study re-emerged in the Federal Register (here). Whatever happened between 2006 and 2011 is anybody’s guess, but I assume that the Bush era FDA leaders axed the proposed study when they learned of it. By September, 2011, these people were on the way out and the door was open again to propose the study anew.

Who’s the Decider? The Patient, the Physician, or the FDA?

What does the pharmaceutical industry think of this? For that, let’s focus on comments that PhRMA made in response to the proposal.

Alexander Gaffney (@AlecGaffney), Health wonk and writer of news for @RAPSorg, summarized the general attitude of PhRMA (see “US Regulators Move Ahead With Planned Study on DTC Marketing“):

In its statement to FDA, PhRMA wrote it was “concerned that the study, as currently envisioned, will not yield information that is relevant to FDA’s regulatory responsibilities to ensure that DTC advertising is truthful, accurate and balanced.”

“Although the study may provide interesting information about the effect of promotional offers on consumer attitudes toward a brand,” explained PhRMA, “it likely will provide little information on whether promotional offers create or contribute to false or misleading advertising, particularly under real-world circumstances or whether additional regulatory requirements are warranted.”

PhRMA’s Comments

If you dig a little deeper into PhRMA’s comments (here), you might be surprised to learn that PhRMA’s position is that “it is the physician, not the patient (my emphasis), who ultimately must decide whether the benefits of the advertised drug outweigh its risks for any particular patient.” Thus, says PhRMA, “the risks of ‘misperceptions’ … should be even lower [PhRMA’s emphasis] for prescription drugs than for experience goods [i.e., a product or service where product characteristics, such as quality or price are difficult to observe in advance, but these characteristics can be ascertained upon consumption] because any potential misperception, of necessity, will be quickly corrected prior to use through consultation with the patient’s treating physician.”

This is a very paternalistic POV in this day and age of social media and patient empowerment. Actually, it is the old “learned intermediary” defense that the drug industry often raises (in the past, less so these days) to shield itself from blame when things go wrong.

FDA’s Response

FDA must respond to comments submitted, but I couldn’t find a direct response to PhRMA’s comments cited above. I did find, however, the following comments and FDA’s response that addressed the issue of the patient-physician relationship generally:

(Comment 22) Two comments mentioned that the study does not assess how consumer perceptions of product risks and benefits are translated into a discussion with their health care provider. One comment stated that because these products can only be purchased after a discussion with a health care provider, the study be redesigned so that consumer perceptions are measured after a discussion with a health care provider.

(Response) We concur that this study does not address behaviors, such as how ad perceptions are translated into a discussion with a health care provider. As noted previously, one purpose of DTC advertising is to motivate consumers to engage in a discussion with their health care provider about health concerns. Another purpose, supported by research findings (Refs. 20 and 21), is to increase awareness of available treatments. DTC advertising does not exist solely in the confines of a doctor’s office; rather, DTC advertising targets consumers outside of a doctor’s office, with the goal of prompting consumers to ask their physicians about the product. In deciding whether or not to discuss a particular product with their health care provider, consumers presumably are engaging in some sort of judgment about the product being promoted. Therefore, clear communication of risks and benefits is needed for consumers before a consultation with a physician, and it is valid to measure these impressions.

PMN116-04

Issue: Vol. 11, No. 6

June 29, 2012

Word Count: n/a

Find other articles in related Topic Areas:

![6 Digital Tools at the Center of Healthcare Digitalization [INFOGRAPHIC]](http://ec2-54-175-84-28.compute-1.amazonaws.com/pharma-mkting.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/6DigitalTools_600px-218x150.jpg)

![6 Digital Tools at the Center of Healthcare Digitalization [INFOGRAPHIC]](http://ec2-54-175-84-28.compute-1.amazonaws.com/pharma-mkting.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/6DigitalTools_600px-100x70.jpg)