“Open Access” Social Media Guidelines for Pharma A Review and Commentary by John Mack

Health Social Media advocates abhor a vacuum, especially when the vacuum is caused by the lack of FDA guidelines for use of social media by the pharmaceutical industry. Although the vacuum was somewhat alleviated belatedly late December, 2011, when the FDA published it’s “Guidance for Industry Responding to Unsolicited Requests for Off-Label Information About Prescription Drugs and Medical Devices” (see XXXX), several more or less independent 3rd parties continue to develop their own guidelines for the industry in the hopes of further spurring the FDA or to bypass the FDA altogether.

In the U.S., the Digital Health Coalition (DHC) is in the final stages of developing its “Social Guiding Principles,” which is being shared with members of PhRMA who have expressed interest in the project. DHC’s 7 dwarf-sized principles have been making the rounds to a select group of insiders and will be made public at the ePharma Summit in NYC this February.

Another 3rd-party (ie. Peter Pitts) version of social media principles for pharma was previously reviewed by me (see “Deconstructing Pitts’ Guiding Principles for Pharma Social Media“). Pitts created 11 principles. However, many of these principles may be very similar to the DHC ones if only because Peter Pitts worked with DHC.

A third set of 3rd-party social media principles was released by Dr. Bertalan Mesko (known as @Berci on Twitter), the founder and managing director of Webicina.com. These “open access” social media guidelines for pharma, which you can find here, were written by an adhoc editorial board of social media advocates with suggestions from “hundreds of collaborators.” The authors are @Berci, Dr. Felix Jackson (@felixjackson), Silja Chouquet (@whydotpharma), Andrew Spong (@andrewspong), Denise Silber (@health20paris), and Rob Halkes (@rohal). It is a distinctly European group of experts, who hope their effort will “facilitate the process for the FDA of publishing its own guide.”

Unfortunately, the FDA is not likely to examine an “open access” document for ideas. Also, the “open access” SM guidelines, like the other two 3rd-party documents mentioned above, are much too vague to be of any use to the FDA. Still, it’s useful to review the Webicina guidelines to see how they might be applied in the real world of pharmaceutical marketing.

The Webicina document breaks down the guidelines into the following 8 categories:

- A Physician’s Rules of Engagement

- Pharma’s Rules of Engagement

- How pharma should use social media

- How pharma should use Wikipedia

- How pharma should use Facebook

- How pharma should use Twitter

- How pharma should write blogs

- How pharma should use Youtube

Can Social Media Replace Face-to-Face Sales Rep and Physician Contact?

Under “Pharma’s Rules of Engagement,” Webicina includes a few guidelines on how pharma should interact with medical professionals. The document states, for example, “A private social media message is often as good as a face to face talk.” In this context, “face to face talk” may mean a visit by a pharmaceutical sales rep. Of course, personal contact between people will never be completely replaced by social media contact. But social media can be effective if sales reps are able to use these tools to communicate with physicians on demand as required (eg, while physicians are on breaks during rounds).

But should pharma sales reps have their own Twitter accounts and should physicians “follow” these accounts and vice versa so that reps can DM (direct message) their physician clients? Maybe it would work. I’m sure that physicians would prefer short 140-character Twitter DMs over long email blasts! And these days, much commercial email ends up in the spam folder never to be opened!

Pharma will no doubt continue to use social media to push messages out to physicians and may even host Twitter chats on topics of interest to physicians (see “AstraZeneca Hosts First-Ever Twitter Chat“). The advice these guidelines give should be self-evident:

- Understand my needs. Make it easy for me to access your expertise and listen to me online.

- Engage with me. Don’t just promote or try to influence me.

- Communicate with me. Using both online and offline channels.

- Protect my private data. Both my personal data and my clinical research data.

- Get my permission. You have my permission when I’ve given it to you.

People to People, Not Company to People Communication

Another suggestion put forward in this document is that when pharma companies use social media, they should “Be human. Ensure that you engage with people as people.” I am an advocate of that idea and have been trying to “out” the humans who are working in pharma and who are using Twitter (see “Pharma Twitter Pioneers Recognized“). But many pharma social media activities are completely non-personal and try to use the brand or company name as something real people will communicate with! It’s not always easy to see who is “behind the curtain” and posting tweets or comments on Facebook. Sometimes, phony people are used to make the conversation seem more personal (see, for example, “Was Lilly’s #mmeds Twitter Chat a Discussion or a Press Conference?“). That, of course, violates the main principle mentioned again and again in the Webicina document “Be transparent. Clearly state who you are and what your intent is.”

For Facebook, the Webicina guidelines state: “Be clear: Provide information about the company with contact details and clearly state who publishes comments on behalf of the company. People prefer talking with a real person, not a brand or a company.”

I see a problem with pharma companies getting too personal and allowing the person behind the curtain to be too visible. First, some companies (eg, Pfizer) claim that they do not have any people (FTEs) dedicated to social media. Several people may share the responsibility of posting tweets, for example. People also leave one company and join another. Nevertheless, I have given my Pharmaguy Social Media Pioneer Award to real people behind the curtain, not the company (see, for example, “AZ’s Tony Jewell Receives 2nd Annual Pharmaguy Social Media Pioneer Award“). I just hope that it helps them when they look for a job with a competitor’s company :-)!

Enable Comments, Don’t Moderate?

The issue of comments on pharma social media sites is very problematic for the industry, which often cites regulations for why comments are turned off on sites like YouTube and until recently on Facebook. We’ve seen a number of instances where a pharma company has gotten in trouble because of comments (most notably on Facebook; see, for example, ‘ “Disgruntled Patient Shuts Down sanofi-aventis Facebook Page“).

The Webicina guidelines, however, prefer that comments be enabled “where possible” (whatever that means). Furthermore, this principle of avoiding comment moderation is reiterated several times in the guidelines: “Avoid moderation. If you have to moderate, try not to pre-moderate and clearly state what you will moderate and why. Publish your moderation policy.”

Pre-moderation, which the Webicina guidelines say may be OK fo blogs, is probably not something many pharma companies have the resources for managing. It may be something that is outsourced, though. Right now, however, it is an extra-added expense that many companies do not wish to have. Several comments form the industry to FDA’s call for answers to its questions about social media favor post-moderation over pre-moderation (see “Answers to FDA’s Questions Regarding Pharma’s Use of Social Media“).

Another, related principle: “Avoid editing comments. Do not edit the comments you moderate as it changes the meaning. People don’t like this. Remove the comment and explain why.” This was another topic covered in comments to the FDA (op cit). It took less than 48 hours for Pfizer to explain why it deleted certain comments on its Chapstick FB page (see “Pfizer’s Chapstick Slapstick Facebook Fiasco“). That wasn’t fast enough, however, to prevent a social media “death spiral” as reported by AdWeek.

Stop When Finished. Is a Campaign Socially Acceptable?

An interesting principle espoused by the Webicina guidelines is “Stop when finished. Close finished campaigns and redirect people to other places.” In some pharma pundit circles, mentioning “campaign” and “social media” in the same sentence is as taboo as saying social media is “just another channel.” Recently, I’ve criticized some pharma companies for abandoning their Facebook “friends” when new rules about comments were put in place (see “Pharma Facebook Pages Being Phased Out: A Good Run While It Lasted!“).

I can see why pharma marketers prefer a campaign with a beginning and an end. They have specific budgets and must achieve a specific measurable goal (e.g, increased market share) within a certain time frame. There are other patient and physician needs that pharma can meet via social media that are NOT compatible with such a campaign mentality. Needs such as how to find affordable medicines, how to get more information about adhering to the treatment and other support issues. It’s not clear who within a pharmaceutical company is charged with meeting such needs or if there is a budget outside control of the brand team for such things.

Wikipedia Editing Rules

On at least one occasion, a pharmaceutical company was caught editing a Wikipedia page about one of its products in order to gloss over some negative studies (see “Web 2.0 Pharma Marketing Tricks for Dummies“). @berci is an expert regarding publishing health information on Wikipedia, so I would take his advice seriously.

One Wikipedia editing guideline suggested is this: “Do not promote. Do not edit an article to promote your medicine.” It may not be so easy to determine if the edit was done to help promote the product or to “correct misinformation.” One person’s idea of “misinformation” may differ from another person’s — especially if the other person is a marketer. Selectively adding only positive information (eg, positive results from new clinical trials) can be considered promotion — in fact, it’s what PR people (who are the pharma people in charge of social media activities) do all the time to “promote” their products.

Webicina offers a better Wikipedia editing principle for pharma: “Suggest edits. Suggest edits on the Discussion page for other editors to make. But you still need to be transparent about who you are and explain your rationale.”

Other tidbits of advice regarding Wikipedia include:

- Be transparent. Clearly state who you are and what your intent is.

- Clarify you intent. Make the rationale for the edit clear in the Edit history or on the Discussion page.

- Speak plainly. No jargon, no technical words. Keep in mind you are talking to people outside your industry.

- Select your audience. Ensure we know who the edit is for clarify which country license applies where appropriate.

- Understand your medicine’s licence. Care needs to be taken when referring to off-licence data to ensure that information is balanced, informative and non-promotional.

- Appoint a specific company spokesperson. To be the point of contact for your medicine.

Rules for Twitter

Webicina et al have a couple of interesting rules for how pharma companies should use Twitter.

“Select your audience. Use different accounts for different audiences so that people can follow content which is tailored and appropriate for them. Examples include investors, shareholders, journalists, job seekers, patients and customers.”

I haven’t seen many pharma companies with multiple Twitter accounts, although I am sure there are a few. Some companies (e.g., Pfizer) may have different Twitter accounts in different countries. But most pharma Twitter accounts are corporate communications accounts that push out information to all the above-mentioned audiences in all countries. I haven’t seen any that are just for patients, for example.

“Publish more than 140 chars. Use longer messages with services like Twitlonger to include additional information.”

This is a good idea that was suggested some time ago (see “Breaking the 140-character Limit of Twitter“). This technique discussed in that article allows pharmaceutical companies to make branded Tweets that will pass muster with the FDA. The “additional information” could be used to mention the brand name as well the important side effects as required by the FDA. However, I don’t see this technique being widely adopted by any of the people or companies I follow on Twitter. I don’t even bother with it myself.

You’re Mad if You Don’t Use Youtube

That’s what the authors of the Webicina social media guidelines think, mostly because Youtube “generates the world’s second largest number of searches after Google itself.” Of course, that has nothing whatsoever to do with the merits of Youtube as a social media platform/channel or whatever. I have often said that pharma’s interest in social media such as Facebook and Youtube has more to do with search engine visibility than with engaging in conversations (see “Drug Companies Are Flocking to Facebook for Eyeballs, Not Conversation“).

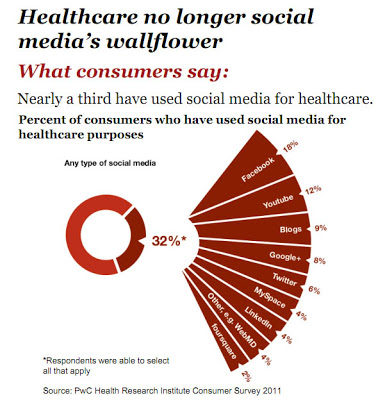

It doesn’t take a genius (or guidelines) to understand the appeal of Facebook, Youtube, and other social media platforms. This is where the “eyeballs” are as demonstrated by this chart from the 2011 PwC Health Research Institute Survey (click on the chart for an enlarged view):

Also see “Ad Dollars Follow Eyeballs to Web.”

I’m not surprised by the percent of consumers who have used Facebook, Youtube, and blogs to get health information, but I am bewildered by the “fact” that more people have used Google+ than Twitter for this purpose. I thought Google+ was dead in the water as a useful social media alternative to Facebook or Twitter. It could be that people chose Google+ meaning Google search because the latter was not an option in the survey. But I can see it now! There will be a rush to Google+ by pharma marketers in order to get in on the ground floor of another social media eyeball fest! In fact, I have heard that some companies are reserving Google+ account names without yet having any specific plans for how they will use it!

PMN111-0a

Issue: Vol. 11, No. 1: January 2012

Word Count: 1196

![6 Digital Tools at the Center of Healthcare Digitalization [INFOGRAPHIC]](http://ec2-54-175-84-28.compute-1.amazonaws.com/pharma-mkting.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/6DigitalTools_600px-218x150.jpg)

![6 Digital Tools at the Center of Healthcare Digitalization [INFOGRAPHIC]](http://ec2-54-175-84-28.compute-1.amazonaws.com/pharma-mkting.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/6DigitalTools_600px-100x70.jpg)