Gamification Now and Then

By John Mack

There’s a lot of brouhaha these days in pharma circles about “gamification” as if it were the newest thing since sliced bread. What is “gamification,” you ask? According to the Gamification.org wiki (here):

“Gamification typically involves applying game design thinking to non-game applications to make them more fun and engaging. Gamification has been called one of the most important trends in technology by several industry experts. Gamification can potentially be applied to any industry and almost anything to create fun and engaging experiences, converting users into players.”

You might find this “Gaming Goes Mainstream” infographic interesting.

Source: business2community.com via Pharma on Pinterest

These days, it may be easier for a pharma company to create a real-life museum educational gaming experience than a virtual world game on Facebook. Way back in 1984, gamification was much simpler.

Gamification Now

About six months ago in December, 2011, Boehringer Ingelheim (BI) teamed up with the Mainz Natural History Museum in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, to create “Ein Medicament Entsteht” (“The development of a medicine”), which was an educational exhibit seen by more than 30,000 visitors who “marvelled at the story of a drug’s development cycle from the first project outline through to market authorisation.” Here’s the YouTube video:

Meanwhile, back in October, 2011, BI’s @johnpugh was tweeting about a “kick-ass [Facebook] game” called Syrum, in which “a player must first investigate molecular compounds at a research desk before putting them to the test in the laboratory, then conduct clinical trials and, if successful, advance a treatment to market.” For more about this game read “BI’s Facebook Game Syrum to be Launched ‘When It’s Ready’.“

It turns out that Syrum has been much more difficult to “bring to market” than the Mainz Museum exhibit. Syrum is still not ready to be played and is “Coming Soon” (see screen shot below taken today when I clicked on the “How to Play” button).

I’m supposed to be a “beta tester” — someone who reviews the game before it is launched to the public — but, so far, I haven’t been given anything to test. I’m afraid this game might take longer to develop and bring to market than an actual drug!

Meanwhile, John Pugh continues to talk about Syrum at industry conferences. Most recently, Pugh presented at “Doctors 2.0 & You™” and he is scheduled to provide “A Detailed Update on the Development and Continued Use of Syrum” at ExL’s 6th Annual Digital Pharma East Unconference on October 17, 2012. Of course, that depends on the gamiification development process, which we know can take years!

Gamification Then

I know from first-hand experience how difficult it is to develop educational games. I started my career — such as it is — back in 1984 designing an educational life science personal computer-based game. It was a simulation of a frog dissection. The objective was to use the keyboard or joystick to move a simulated hand, pick up simulated instruments, and “dissect” a simulated frog and identify its organs. At the end, the user (usually a high school biology student) was challenged to reverse the process by putting the frog back together (the game aspect). If successful, the user was rewarded with a fun animation of the (simulated) frog dancing off in a top hat and cane — no harm done (except to the frog I dissected doing research for the simulation). The codename was “Defrogger” but it was published by Scholastic as “Operation: Frog”.

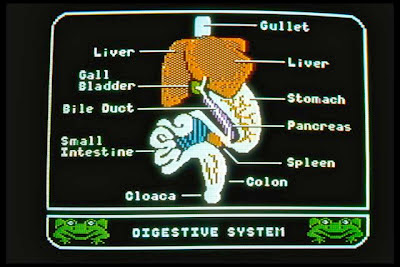

Operation: Frog ran on the Apple II computer, which at the time had the most advanced graphics of any personal computer on the market. It was an 8-bit computer with a screen resolution of 280×196. You could get 16 colors using a technique called “dithering.” Here’s a screen shot showing the frog’s digestive system:

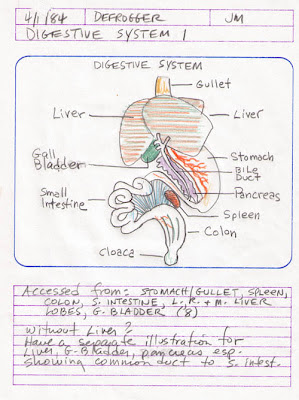

You can count the pixels without a magnifying glass! To get this level of detail from an 8-bit 16-color computer display was quite a challenge requiring planning and storyboards (I also created the graphics and wrote the screen text and user’s manual). Here’s the storyboard for the dissection screen, which is evidence that I actually did this more than 28 years ago (OMG!):

In my proposal to Scholastic I said that “dissection of a living animal or one stewed in formaldehyde is an unpleasant experience for many biology students and teachers alike. Not only does it require the sacrifice of many animals, it is also expensive and potentially dangerous. Consequently, many children never carry out a dissection.”

Okay, I was playing it up a bit too much. However, the program was a hit. It was featured in the October 15, 1984 issue of Newsweek Magazine and played a role in a 1987 California court case in which Jenifer Graham, a brave 15-year-old high school girl, defended her right to refuse to dissect a frog. Ms. Graham suggested “she could learn just as much from models or computer graphics as her fellow students learn from the dissection of a frog. It seems incredible,” said a Los Angeles reporter at the time (here), “that a school would resort to a dead frog, formaldehyde, forceps and scalpels in this age of computer graphics.”

At the time, Ms. Graham was vilified. Unfortunately, although we’ve come a long way in terms of computer graphics and gaming, students who refuse to dissect real frogs are still vilified (see, for example, “Middle school student claims teacher bullied her over refusing to dissect frog“).

For more Operation: Frog screen shots, see my Pinterest Gamification Board.

PMN117-03

Issue: Vol. 11, No. 7

July 26, 2012

Word Count: n/a

Find other articles in related Topic Areas:

![6 Digital Tools at the Center of Healthcare Digitalization [INFOGRAPHIC]](http://ec2-54-175-84-28.compute-1.amazonaws.com/pharma-mkting.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/6DigitalTools_600px-218x150.jpg)

![6 Digital Tools at the Center of Healthcare Digitalization [INFOGRAPHIC]](http://ec2-54-175-84-28.compute-1.amazonaws.com/pharma-mkting.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/6DigitalTools_600px-100x70.jpg)